In search of a prosthetic revolution: from charity to investment

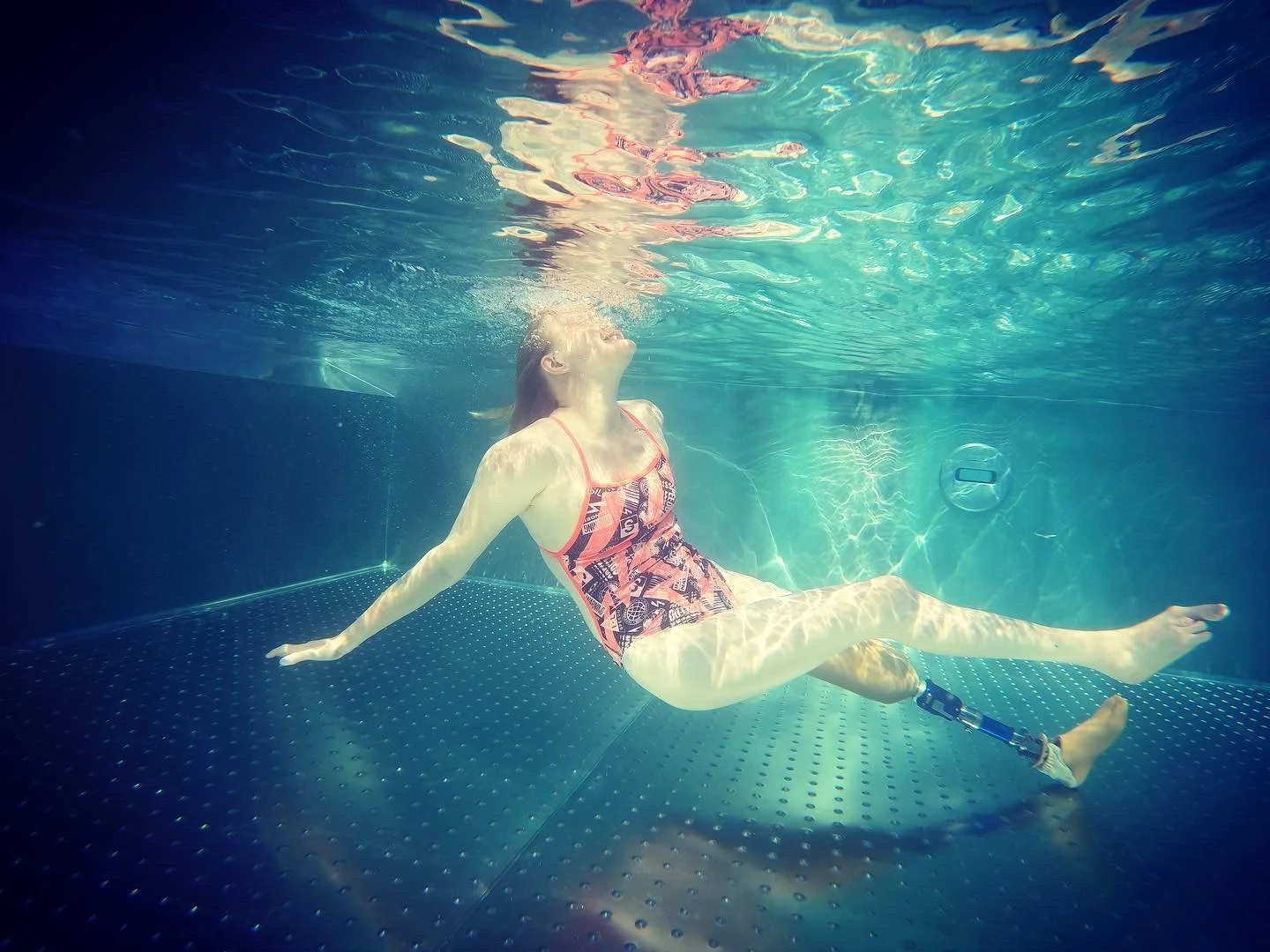

By Susannah Rodgers MBE, Paralympic Gold and Bronze Medallist in Swimming, Technical Adviser on Disability Inclusion and Prosthetic/Orthotics user since birth

On Sunday 5 November, the world marks International Prosthetics and Orthotics Day. Having access to appropriate prostheses and orthoses can change a person’s life, allowing them to participate in all aspects of society and their community, including education, work, family, access to health care, and much more.

I know this only too well from a personal perspective. I have worn prosthetic limbs on my left side (both my arm and leg) and orthotic devices for my right foot since I was born with congenital amputations and malformations.

There are an estimated 65 million people with limb amputations globally. Each year, 1.5 million people undergo amputations - mostly lower limb - and most amputees need access to prosthetic services. This is expected to double by 2050. An estimated 64% of people living with amputations are in low- and middle-income countries.

I have lived a life as an amputee and prosthetic limb user, which has led me to the highest levels of achievement in Paralympic swimming and sport, and also in my professional life and beyond. It has also not been without its constant challenges.

Susannah with a Chevening Scholar, through the FCDO Chevening Scholarship programme, who is also a prosthetic limb user.

Photo credit: Susannah Rodgers

On the one hand, I am hugely grateful and privileged to live an independent life, to have access to artificial limbs and orthotics through the UK health system and to live my life fully in society, both professionally and personally. However, we have a long way to go in this industry to make it more transparent, competitive, accessible, with products that are adaptive to the user, suitable for the context, and which are available and affordable.

Innovation looks exciting when we see campaigns about 3D printing and robotic designs at academic institutions and small-scale start-ups, but the reality is that these products reach the very privileged few due to the sheer cost and time it takes to get them to market and within broader health systems.

Creating opportunities for disabled persons globally

Many people are surprised by how much my leg and arm cost in terms of component parts, as well as the human power needed to produce them through technicians, prosthetists, and orthotists. I also create a number of jobs to facilitate my independent living, which is the same for many persons with disabilities who use different assistive technology and devices in their lives. However, this important fact seems largely ignored by governments, corporates, technology giants and innovators who tend to focus more on enhancing the human power of non-disabled populations through various technology and devices (due to the bigger return on investment), rather than focusing time, resources, energy and efforts on levelling the playing field and creating opportunities for disabled populations globally.

It is not just money that is needed. A huge amount of time is involved in making prosthetic limbs, in particular because they are a feat of engineering and science. I can spend anywhere between one to four years getting a new leg made and people wonder why I have to be so careful not to gain or lose weight: if my leg does not fit, I have to spend a huge amount of time in clinics having a new one made. The process is slow, open to error, and sadly can take a lot of time to get right. All these things can really impact people’s mental health, especially if anyone has fluctuating weight and their limb simply does not fit. These are the added pressures faced by so many amputees and prosthetic limb users on a daily basis.

And I live in a so-called high-income country and am very lucky as a result. In low- and middle-income countries only 5-15% of people that need a prosthetic limb actually have access. High prices, travel costs to services, and the very limited availability of prosthetic services make it unaffordable and inaccessible to many people in need.

Frequently, there are no trained personnel available to work in this sector. In many countries, including some high-income countries, the provision of prosthetics and orthotics can be restricted by product availability and budgets within extremely stretched health systems. This can mean that individuals are not living life to their fullest potential and with regular trips to hospitals and clinics, it impacts their daily lives.

Calling for public-private collaboration, investment and innovation

The market for prosthetic solutions in low- and middle-income countries is small because prostheses need to be customized and fitted through a service delivery process requiring specialized infrastructure and personnel; both are in short supply in these countries. Governments have historically not invested in this sector, because they lack data and awareness of the need and economic benefits. Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) sometimes provide prosthetic services, largely in response to emergencies that sometimes operate in parallel to government systems, but charity is not the solution and a public and private collaborative approach is needed.

Susannah at the United Nations. Photo credit: Susannah Rodgers

We need to consider the economic and social benefits of investment in this sector and encourage more private sector and technology innovators to join this space and provide solutions. Over the years I have appealed to academics, NGOs, donor funded organizations and the private sector to come up with innovative solutions to various challenges I have faced wearing my prosthetics but for the most part these conversations have ended in no action. I believe this is because it is not viewed yet as an exciting investment opportunity.

However, if governments can see the potential of persons with disabilities who are economically active contributing to between 3-7% of GDP, not to mention the value they create through the people employed to design, build and create their prosthetics and orthotics, then we may start to attract more interest and figure out ways to create innovative products that are efficient, cost-effective and durable rather than one-off exclusive and novelty products.

This sector needs a rethink and I call on those working inside and outside of the assistive technology sector to hear my call to action and join me in a prosthetic revolution.